By Gregg Stopa, AIA

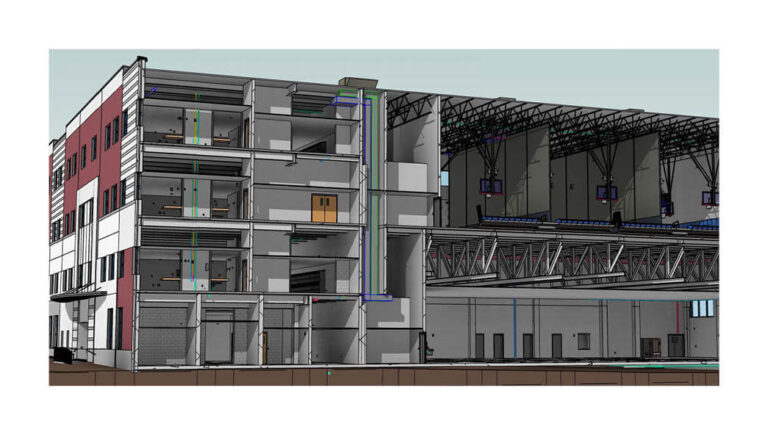

I’ve been with DMR Architects for 23 years, recently becoming a partner in the now 25-year-old firm. This milestone inspired reflection about the architecture industry. For the most part, how buildings are being built is the same. Design-build projects and some new equipment provide a means to go a little faster, perhaps, but building is still all about the steel, sheetrock, concrete, wood and bricks.

Architectural services, on the other hand, have expanded and evolved to the point where the architect of the 1990’s might not recognize the profession today. The most significant change is in information technology, which creates productivity and expedites communication, but also unnecessarily adds a level of stress and complexity.

First, the expectation of responsiveness pressures every facet of our service. Driven by information technology and financial structure, projects now are developed in a context that would be impossible 25 years ago. The Internet contains more information than any architect or person could possibly know. The number of suppliers, products and processes is infinite. We find frequently that clients discover prospective solutions—sometimes when there is no problem to solve—that are not even relevant, never mind applicable, to our work on their behalf. But the requirement that we address the issues is very inefficient and disruptive. And financial structures today impose an enormous pressure on our clients to complete projects at budget and on time, despite variables that are beyond anyone’s control are ever-present. The architect’s function is unrelated to these dynamics but become influencers in how our work is delivered.

Being able to work virtually from anywhere digitally creates a set of expectations for responsiveness that has caused us to change how we operate the business. Because most of us use our own personal devices for work phone calls and emails, we also have seen our workday creep longer. 25 years ago, we received and delivered documents or materials by hand—often through regular mail. 25 years ago the client called us at our desk to confer. We could only get mail once a day. Now we have developed a mindset of being ready to perform virtually on-demand.

These expectations and the technology that fomented them come with many benefits, including a massive improvement in productivity. Is the work any better? Of course, styles change, but good work always looks like good work even when it ages. User specifications, especially in health care and other technical fields, are far more complex than they once were and the efficiency demands on space are far greater. Our profession has not just responded to those demands, we developed design strategies that improved our clients’ businesses and led to new performance standards and real estate practices.

In that sense, the architect has not changed. The architect is still the person that figures out how it should look, what it should be made of and how it should get built. So while the architect of 25 years ago would be lost if transported to today—and the architect of today similarly lost if transported to 25 years ago—the object of our profession is the same. Like everyone else, we are just expected to work harder at it and be better at it than ever before.