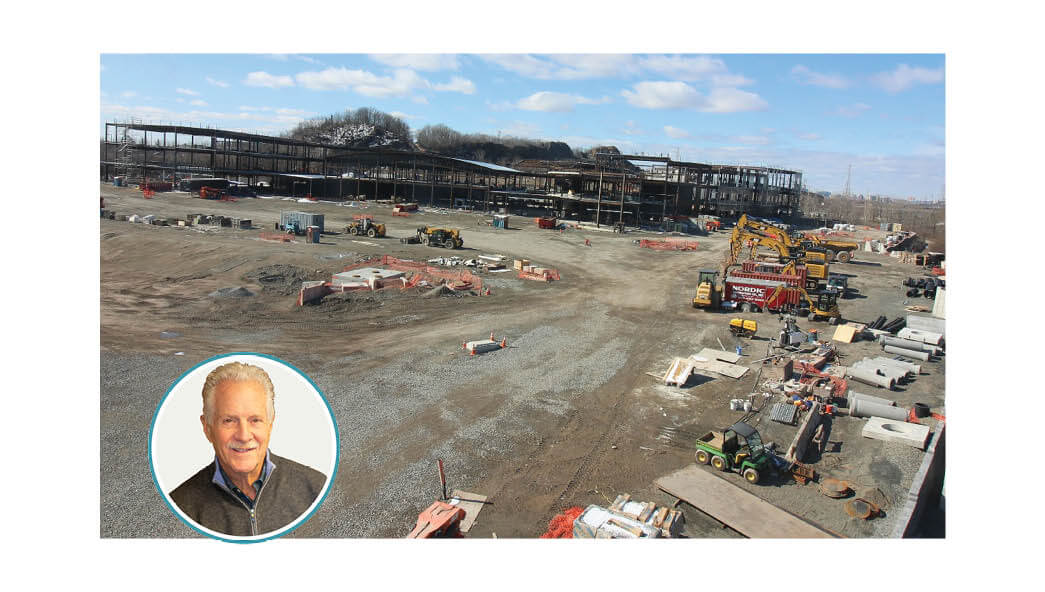

Architecture is a continually stimulating profession, especially for the firm’s owner who addresses complexities in various industries in delivering the service. Most people correctly associate architecture with creativity, as design is at the core of our profession, but the business of architecture incorporates numerous skills and processes beyond aesthetics. No where is this more true than DMR, which is larger and more diverse than most architectural firms, and integrates engineering, planning, environmental, bidding, construction supervision, legal and more into our service mix.

But it does always come back to design, because that is our deliverable. A subject of much discussion in every project, the challenges of design begin not with a blank canvas but with a set of constraints: space limitations, functionality, budgets and available materials are just four of the variables that are addressed by the architect. The real estate business positions the architect as the natural pivot point between the property owner and the contractor, so not only are we engaged for design, the architect is largely focused on managing the business issues of real estate development.

The architect’s role in development has never been greater than in the current environment, where regulatory standards have grown in complexity. For example, in New Jersey, various government agencies responding to Superstorm Sandy have adopted regulations on flood plains that can undermine the viability of projects already on the drawing board. And among other issues we have encountered this year, the unexpected presence of migratory birds prevented us from removing trees, postponing construction. Unknowns adds risk to development, and one of an architect¹s functions is to foresee potential issues and plan around them, eliminating the risk, but it is not always possible.

And finally, there is the variable represented by the market itself. Construction materials and labor costs can change after the planning for a project, but before it is commenced. The architect must monitor these issues so that there are no negative surprises after construction begins. And projects that seemed to be in demand when planned might not find a robust market when completed. All of these issues and many more must be factored not only into our service to our clients, but in the management of our architectural practice.

After 25 years in business, over which time DMR has become the 4th largest architectural firm in New Jersey, we’ve seen multiple cycles in the real estate industry. No economy is like any other, making it impossible to predict the length or impact of an expansion or a contraction. The correct management policy is to be ready to respond to changes in either direction always looking for the best position for future growth. Even when the business climate is in a downturn, there is a right way to contract that allows architects to take advantage of the inevitable opportunities to grow.

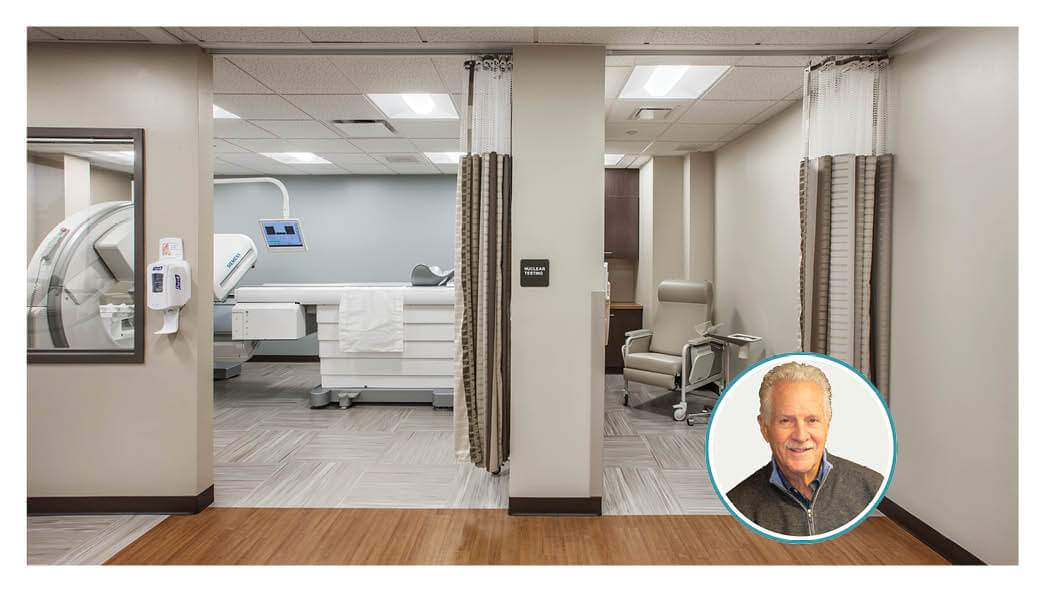

At DMR the main principle of stability is depth and diversity. We have structured the firm to weather downs and maximize ups by being able to shift into various practice areas depending on the demand cycle. In expansions, office and residential work is plentiful. In contractions, education and healthcare work may not be as plentiful but technology advancements often lead to redevelopment. By maintaining a staff that has expertise in a broad array of practice areas, we not only protect the stability of our own firm, we provide our clients with a depth of institutional knowledge that can only be developed through taking good ideas from one area and applying them to another.

A complicated business? Yes. But a rewarding one, especially when the day comes that a project is complete and we see it not only for its excellent design, but for all the elements that we blended into accomplishing its development.