By Joshua Burd

By Joshua Burd

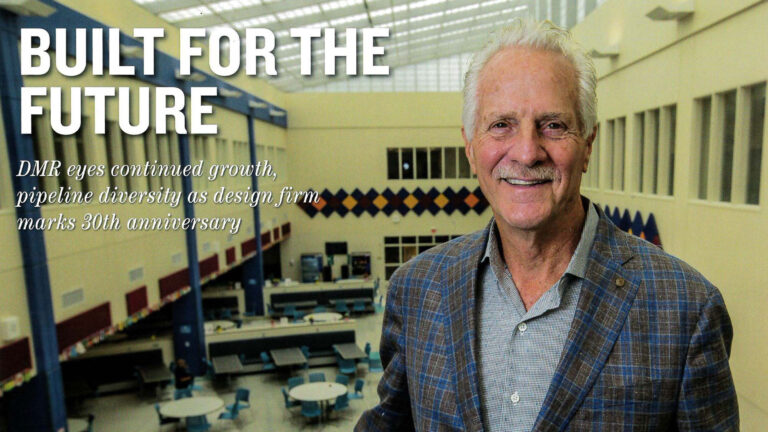

Lloyd Rosenberg walks through the halls of the Frank J. Gargiulo Campus in Secaucus with an obvious pride, pointing out everything from the color scheme and curvature of the hallways to a fully equipped teaching kitchen for students at the 350,000-square-foot high school.

His affinity for the space is understandable. Completed in 2018, the $150 million complex is not only a signature project for his firm, DMR Architects, but the largest of its kind for a practice that has spent three decades designing educational facilities.

“The firm was founded doing schools,” said Rosenberg, DMR’s CEO and president. “If you look around this building, you see that … it has a great number of elements — colors, materials, acoustics — that are a higher end of creativity than a typical school building.”

Education remains a cornerstone of DMR’s business, as evidenced by the state-of-the-art vocational school, but the firm is now every bit as prolific in sectors such as multifamily, government, health care and interiors. That growth has helped it build a portfolio of more than 3,000 projects since its founding — as the practice marks its 30th anniversary — and a current pipeline that spans 200 projects valued at more than $1 billion.

That means there are likely more milestones to come for the Hasbrouck Heights-based firm, which has grown from a team of three to 45, whose services now range from design to redevelopment planning.

“We’re busier than we’ve ever been — across the board,” Rosenberg said.

The Jersey City native started his career in the mid-1960s after attending the acclaimed College of Architecture at the University of Oklahoma. Fittingly, his first major project after returning to New Jersey was the new Glen Ridge High School, he said, recalling a design that involved a large cantilever overhang at the main entry and a central library surrounded by classrooms.

Rosenberg would spend the next 25 or so years working on not only schools, but on office, residential and other project types, building a diverse foundation that would guide the rest of his career. Still, it was education that helped him launch DMR in mid-1991, in the wake of a recession, as a three-person operation.

“There was not a lot of work in the business to go after,” he said. “I was lucky to get some of the school clients that I had to continue with us to do their work.”

Among its early projects was a new Sparta Middle School, a 127,000-square-foot facility that would open in the late 1990s. The local school board retained DMR early in the process after voters approved the project, which would become the largest building in Sussex County at the time and showcased the firm’s capabilities.

“I felt like I had hit a milestone doing that,” Rosenberg said, noting that the firm had only about 10 employees at the time, making it all the more notable to work on the roughly $35 million project. It was also a chance to bring high-end design to a school after a period — starting around the 1950s, he said — in which aesthetics had seemingly faded from public buildings.

Even with the milestone, Rosenberg saw the need to branch out.

“It was important for us to diversify our practice because the last thing we want to do is specialize in one particular area and then when that area dries up … we run out of work,” he said. “In my career I’ve seen some of those spikes and highs and lows, so we purposely diversified in all of these other areas.”

That was no easy task for a firm that was “known as a school architect,” he said, but DMR succeeded in the years that followed. Rosenberg attributes that to key hires such as Pradeep Kapoor, who has spearheaded its growth in areas such as government and public safety, which were a natural choice due to its experience with school districts. That has led to a long list of projects such as the Bergen County Public Safety Operations Center in Mahwah and the Jersey City Justice Complex.

Additionally, Rosenberg cites the growth of DMR’s multifamily residential practice, which has designed 10,000 units in New Jersey in recent years, amid an ongoing apartment boom that is poised to continue. That has included everything from Russo Development’s conversion of the historic Annin Flag factory in Verona to new midrise rental buildings throughout the state.

“We can’t build enough multifamily housing,” said Rosenberg, who hopes to see the pace continue for at least the near future. “I’m old enough to know that it doesn’t last forever, but we’re certainly taking the ride right now.”

The past decade has also seen the growth of DMR’s redevelopment and municipal planning practice, which is best-known for crafting a rehabilitation plan for Hackensack’s downtown. DMR’s team has guided the city’s efforts to create a mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly environment around its aging Main Street corridor, helping to attract developers and resulting in more than 3,500 new apartments completed, under construction or in development in the district.

The effort has also yielded new community and outdoor public spaces, plus improved pedestrian and automobile circulation by bringing two-way traffic back to Main and State streets.

“From my perspective, the city had great leadership and was willing to listen to new ideas and opportunities,” Reiner said. “We were at the table when all of those things happened, so that was really both personally and professionally very rewarding, and the city has supported what our plans were and we’ve had great success there.”

Reiner, a partner and senior urban designer with DMR, credited Rosenberg for supporting the growth of the practice and having the vision that being a leader in planning and redevelopment would “provide the firm with a pipeline of opportunities from an architectural standpoint.” To be sure, the platform began to expand in earnest around 2015, bringing the firm to municipalities ranging from Elmwood Park to East Brunswick. It now has about 100 active planning projects in a given month, Reiner said, thanks in part to its ability to offer both design services and consulting in areas such as zoning, construction pricing and navigating the state’s redevelopment law.

“I think we look at a broader picture,” he said. “It’s usually a problem or an issue that the municipality has to solve and we believe we bring a lot to the table in helping them solve that problem. As opposed to just solving the problem for the architect or solving the problem for a planner, we’re trying to solve a problem for how you finance it, how you get it built, what’s the timeframe, what’s the cost — all of those things come into play.”

DMR’s planning and residential practices are now intertwined as integral parts of its pipeline going forward. Look no further than communities such as Ridgefield Park, where the firm developed the master plan for the mixed-use, 55-acre Skymark Town Center, while designing a 19-story high-rise in the borough with 552 apartments.

Its foothold in education also remains as strong as ever. Having completed more than 1,000 school projects to date, equating to more than $900 million in development, its pipeline in the sector now comprises roughly $325 million in activity. That includes new schools in Plainfield, Paterson, Carteret, New Brunswick and Jersey City, as well as 25 upgrade projects in New Jersey and 40 in New York City.

Even DMR’s corporate interiors practice is busy, Rosenberg said, despite the uncertainty caused by the pandemic. As it were, he said the firm is fortunate that COVID-19 impacted its pipeline far less than anyone had feared.

“We were worried about what was going to happen, but we didn’t have any breakdown in projects or clients. I think it was more about managing the staff and managing people,” Rosenberg said. He added that the firm was about 90 percent remote for the first few months of the crisis before bringing team members back to the office for much-needed collaboration.

The diversity of DMR’s portfolio has been critical to withstanding the pandemic and other past downturns, which is a point of pride for Rosenberg. He’s also proud of how his team has grown in recent years, he said, noting that “I would hire more people if they were available.”

“Finding good people right now is very hard,” he added, but he believes that the firm’s multidisciplinary platform is a key draw for prospective employees.

“One of the things we like to consider with staff is that they don’t get pigeonholed into a particular area,” Rosenberg said. “So a young architect that comes into the firm, if they’ve always done houses (but) they want to see other things, we offer them the ability from project to project to work on different things so they get experience, they get knowledge. They may eventually like one particular area and become better at it than others.”

This article was written by Joshua Burd and originally appeared in Real Estate New Jersey.