Written by Christine Fisher. Produced by Brandon Bagley.

There’s a Nelson Mandela quote that reads, “There is nothing like returning to a place that remains unchanged to find the ways in which you yourself have altered.” In a way, Lloyd Rosenberg, founder of DMR Architects, has done just that.

When Rosenberg founded DMR Architects in 1991, the first buildings he designed were schools. He had been designing them since graduating from architecture school, and he’d amassed potential clients who agreed to give his new company a try.

Twenty-five years later, Rosenberg is still building schools, returning in a sense to his roots, but lots of other things have changed. For starters, DMR Architects has diversified, and it’s become a leader in green building.

Hudson County’s $144 million high school

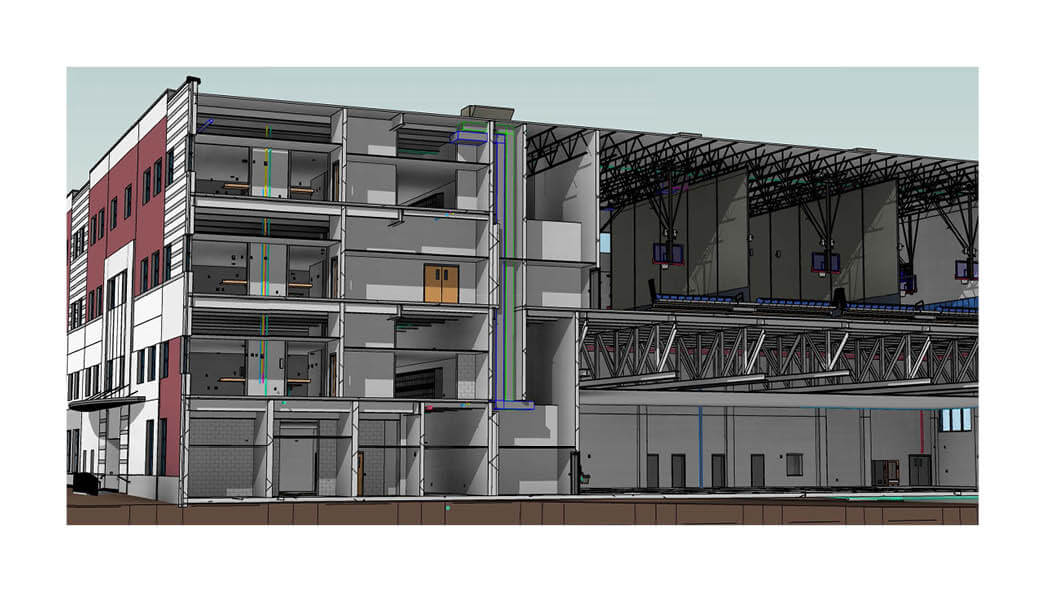

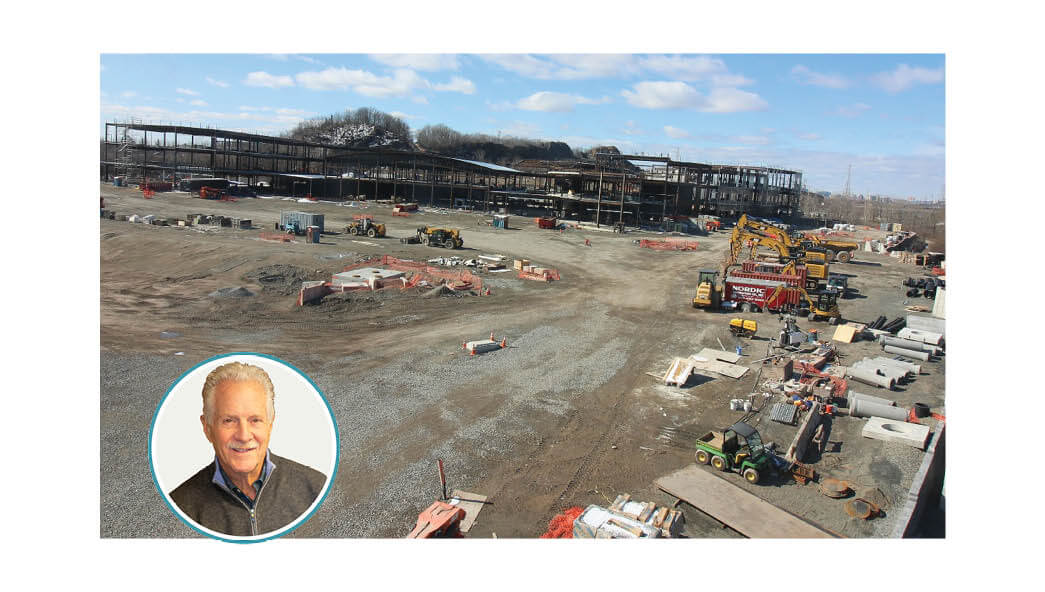

In 2016, DMR Architects celebrated its 25th anniversary, a milestone Rosenberg is especially proud of. The company has a staff of 40, and is currently building a $144-million high school for Hudson County, New Jersey.

“The high school we’re doing now is spectacular. It’s going to be a building that’s going to set the bar for high schools throughout the country.”

DMR Architects is the lead designer on that 350,000-square-foot design-build project, for which it’s seeking LEED Platinum Certification.

“The high school we’re doing now is spectacular,” Rosenberg says. “It’s going to be a building that’s going to set the bar for high schools throughout the country—the technology and programs and infrastructure and energy savings, all the things you’d want to put in a school.”

The building will have solar power, geothermal heating and cooling, a partial underground garage for employees and water retention systems. A roof will capture storm water to irrigate landscaping, and all of the mechanical systems are being built with the best green building products on the market.

The building was designed to suit what educators hope to teach, and it will have a fabrication lab, applied science labs, a television production and radio broadcasting studio, digital media labs, a culinary lab, architecture and engineering labs, a hydroponics lab, musical theater, a dance and drama studio, yoga, judo and other fitness rooms.

Rosenberg has always designed schools, but now the green technologies, and the administrators’ willingness to embrace them, have changed.

An easier pitch

Rosenberg has designed thousands of schools and public and private buildings in New Jersey, and says he was “very much in the forefront” of sustainable design.

In the beginning, he had to make presentations explaining why green buildings cost more than traditional buildings. In the early ’90s, when DMR Architects started, green buildings often cost 10 to 30 percent more.

“I don’t have to make that pitch anymore,” Rosenberg says.

Today, he says, the difference between an energy-efficient building and a non energy-efficient building is almost negligible. That’s partly because all of the required products are readily available.

“The cost is in the certification, the paperwork, the testing, going back and doing some examinations and reports to prove that it’s been done [right], but the basic building doesn’t cost any more, it may even cost less,” Rosenberg says.

The motivation has changed, too. DMR Architects’ first green building clients sought LEED Certification as a marketing tool. Clients today opt for green buildings to save money through energy efficiency and utility savings.

The benefits of diversifying

DMR Architects has taken on medical buildings, public and private buildings, institutions, even a train station.

“I’d always hoped to be a midsized architectural firm that was diversified in what we do,” Rosenberg says.

He sought variety so that staff wouldn’t feel pigeonholed in one sector and to help protect the company during economic downturns. At times, the residential market has boomed for a few years and then gone flat. At other times, it’s been the public sector.

Outside of providing resiliency, trying out different sector projects has given perspective. Clients benefit from that different view, Rosenberg says.

“We built a train station, not necessarily in our sweet spot, but we were actually complimented because we took a fresh approach, not one that someone had done over and over and over again,” Rosenberg says. “We actually proposed to the user a different way of doing something, which they embraced, and now it’s the standard for them.”

Shared success

The firm makes a point of hiring “top talent from the top” and “top talent from the bottom,” which gives it the experience of senior staff and the technological expertise of recent graduates. While the new hires helped more experienced employees stay relevant, the senior people help new hires “learn what they don’t know.”

“I love young people that come in with enthusiasm,” Rosenberg says. “They want to learn and the more you throw at them the better job they do. I love to see people who came here as a graduate and now they’re project managers. I’m proud of those people that I’ve given the opportunity to do it. I’ve helped them, but they’ve really done it on their own.”

When DMR Architects turned 25, the firm hosted a series of employee-engagement activities—like a company boat ride and company picnic—to celebrate not just the success of the firm, but the success of its individual employees.

“When we started in 1991, we had three people; we now have 40,” Rosenberg says. “People that are here have been with me some 24 years. Most of the staff has over 15 years with the firm… so I think it’s successful when you have the vast majority of the staff that has been here that long.”

This article was originally featured on US Builders Review.