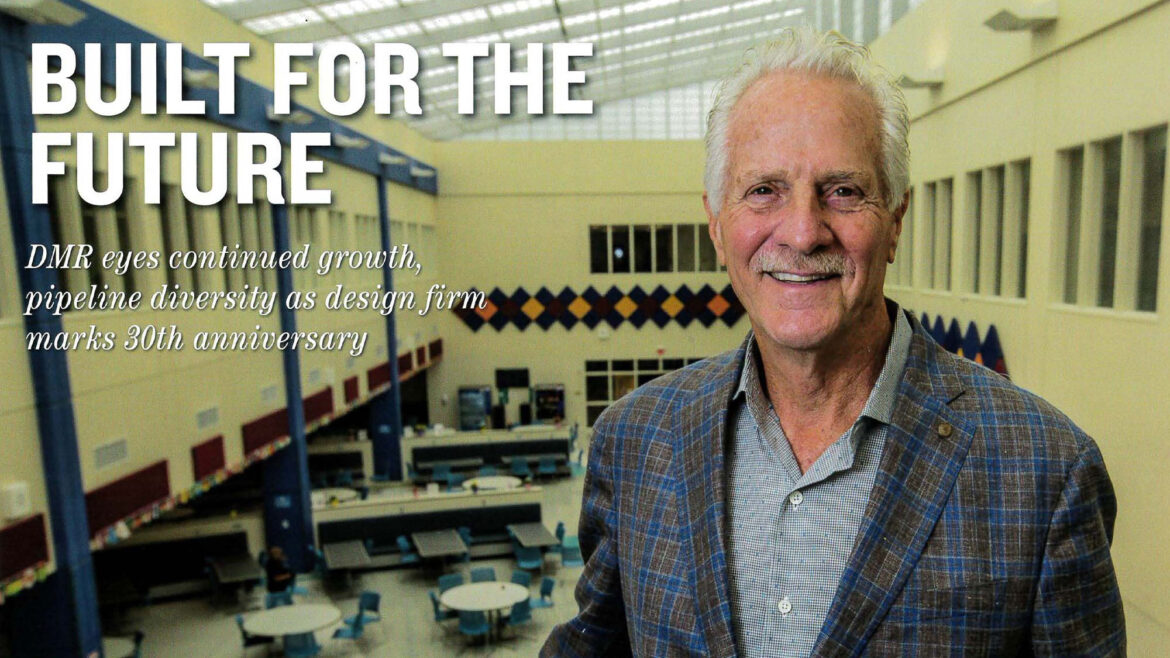

On January 3 DMR named Pradeep Kapoor, AIA, LEED AP BD+C President & CEO, becoming only the second person in the firm’s 32-year history to serve in that role. Pradeep succeeds Lloyd A. Rosenberg, AIA, the visionary and driving force behind the firm that we know today.

As a new era begins, we look back on the other projects and moments that changed the course of our firm.

By Joshua Burd

By Joshua Burd

My career prior to founding DMR provided a wide variety of experiences and projects that were excellent preparation for creating and running the practice we have today. I built an entire city in Nigeria, where I would spend three months at a time and once even hid out in a safe house during a coup. I also designed a $100 million luxury apartment complex that received attention as the units were rentals, an uncommon concept at the time.

My career prior to founding DMR provided a wide variety of experiences and projects that were excellent preparation for creating and running the practice we have today. I built an entire city in Nigeria, where I would spend three months at a time and once even hid out in a safe house during a coup. I also designed a $100 million luxury apartment complex that received attention as the units were rentals, an uncommon concept at the time.