By Kurt Vierheilig, AIA, LEED AP BD+C

According to the most recent Arts & Economic Prosperity report by Americans for the Arts, when we fund the arts, we are not supporting a frill or an extra. Rather, we are investing in an industry—one that stimulates the economy, supports local jobs, and contributes to building healthy and vibrant communities.

By working with DMR Architects, municipalities have been able to use their existing and new buildings and green spaces to provide unique performance spaces.

In Englewood, the recently completed renovation of bergenPAC was informed by the board’s goal to rejuvenate the outdated facility while preserving its cultural significance to Downtown Englewood.

The resulting aesthetic is a blend of modern and traditional elements including exposed brick walls, marble on interactive bar areas, bronze detailing and wood paneling paired with exposed ceilings and hanging lights to give it a current vibe.

But before we got there, we were faced with a situation we as architects are frequently tasked with: They knew what they wanted but weren’t sure how to get there. We worked with them through a few iterations of design, renderings, and samples to help them understand and translate their vision into a reality. It was a process to get there but the result exceeded all expectations with our client calling the experience, “a harmonious marriage of architecture and the performing arts and a testament to the power of design as inspiration and elevation for the human spirit.”

The unique juxtaposition of materials contributed to an improved pre-show experience in the public entry lounge, as well as in a newly created VIP entertainment area with its own entryway. The atmosphere upgrades throughout have resulted in people coming earlier to gather before entering the theater space and more repeat visits, and the new VIP area also allows the facility to host exclusive events like meet-and-greets with talent. It has also elevated bergenPAC as part of a visit to Englewood that is known for its upscale shopping and dining and is now attracting a higher caliber of talent that fills its calendar throughout the year appealing to a wider demographic including young professionals looking for a night out as well as parents looking for family entertainment.

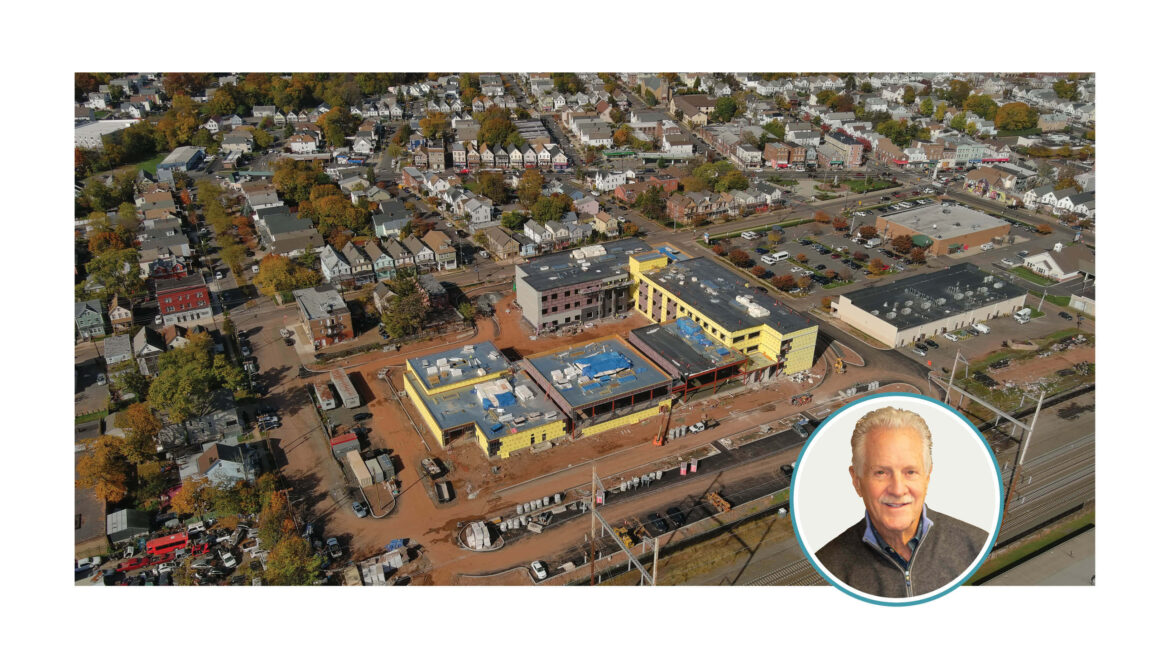

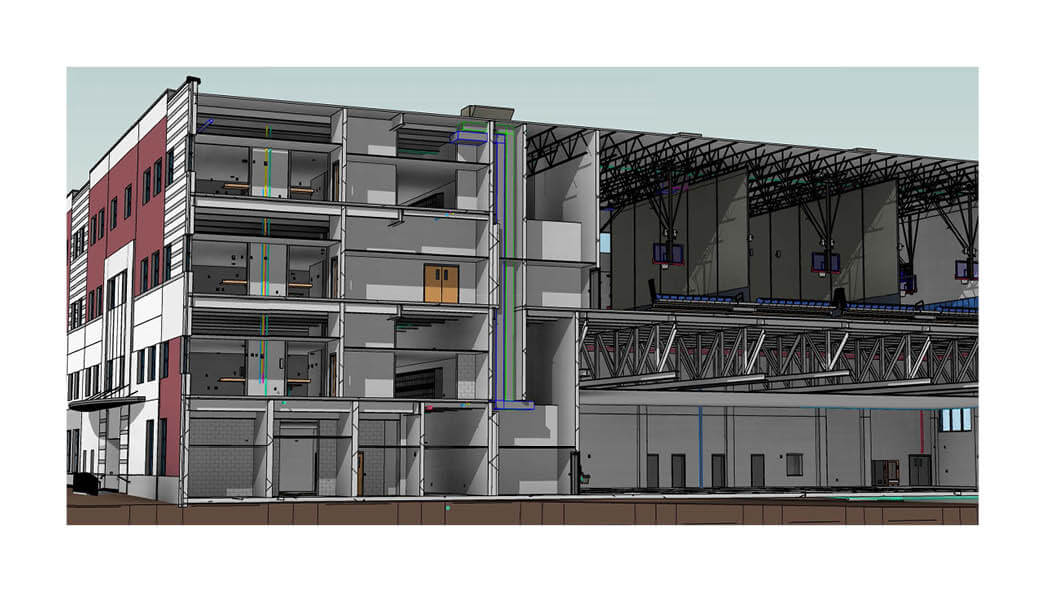

We also worked on the award-winning repurposing of Hackensack’s 140-year-old Masonic Temple into a 224-seat performing arts center. When we began working with the city on its downtown redevelopment and rehabilitation plan in 2012, it stressed that the inclusion of civic elements and public spaces were key to the city’s success.

Hackensack’s previous facility was somewhat makeshift, in a space that wasn’t located, designed or configured to function as a theater or to inspire placemaking. As part of the planning process, we suggested that the city should purchase the more centrally located Masonic Temple and adjacent parking lot as a replacement for the original PAC.

Interior design anywhere—but especially in performance spaces—is about igniting as many of the senses as possible including visually pleasing design, comforting materials for seating, and incorporating the best acoustics. It’s important to create a cohesion to enhance the experience for theatergoers.

The redevelopment of the Masonic Temple’s interior allowed them to create a robust entertainment calendar and was central to the plan that has since attracted retail and dining businesses as well as developers who have since built thousands of residential units.

The Hackensack PAC’s interior upgrades were complimented by the conversion of the adjacent parking lot into Atlantic Street Park, an urban green space where those who live and work in Hackensack can enjoy nature as well as municipal events like movie nights and free concerts at its amphitheater.

In Woodcliff Lake, DMR designed concepts for a two-acre, municipally owned parcel into the first borough-owned park that was expected to transform the downtown. In addition to the trails and expanses of green space that would be expected in a park, the plans included an amphitheater that would allow the borough to host musical and theatrical performances, attracting visitors from all across Bergen County and beyond.

The Performing Arts Centers in Englewood and Hackensack have achieved what The Arts & Economic Prosperity report by Americans for the Arts says they’re for: vibrant arts communities attract visitors who spend money and help local businesses thrive. They also keep residents spending money local-a value-add that few industries can compete with.

A version of this article originally appeared in NJ Municipalities.